You can’t stream The Elephant Man (1980) anywhere, as of this writing, and I think that’s great. Everything has lost its value in our world of overabundance. We could use a little more friction.

David Lynch took the power of dramatic withholding seriously, and that extended to his home releases as well as his cinematic work. His DVDs did not allow the viewer to skip chapters, so that they would have to watch the film as he intended and not break his work into pieces. The whole arc and character development had to be respected.

Respect is not something that I associate with most major streaming companies (I will mention some notable exceptions - Criterion Channel, MUBI, Metrograph, Kanopy - and yes, I just used dashes even though I am human). The major streamers don’t necessarily respect their viewers, or filmmaking in general, so why should they get to make money with a film that gets to the heart of human dignity? If you want to watch a film of this magnitude, you have to work for it. At least a little bit.

The Screening Room

I watched the film on the big screen at Metrograph in New York City, and they still have a few upcoming showings, if you’re around. I’m always arguing for the primacy of theatrical viewing when possible, especially for older films, and this one really delivered. Lynch is a cinematic world builder, so to fully appreciate his films, you must cut off the real world and immerse yourself in his. If you watch it at home, turn off your devices and lights and become transported.

How do you find acceptance in society? Most people try to blend in and then ask why they are overlooked, but what if you can’t be ignored? What if you are so different that everyone stops what they are doing and screams when they see you? In our day-to-day lives, most of us can hide our ugliness because it’s hidden inside our heads, seeping out in anonymous online forums or comments sections.

Good cinema takes quotidian problems and pushes them to the dramatic extreme. We need this exercise to question our beliefs and assert our world views in order to answer the biggest questions of existence. Why are we here? Where are we going? Why do we tear others down to feel better about ourselves? Do we really exist so that we can just stare at our phone?

Cinematographer Freddie Francis, BSC

The black and white cinematography by Freddie Francis, BSC looks incredible, especially blown up in the theater. He shot on Kodak Plus-X stock but had to do extensive testing with several British photo-chemical labs as their equipment had fallen into disrepair with few films shooting in black and white.

Francis told British Cinematographer,

“Rank’s processing produced a result which immediately filled me with confidence. My first impressions were that the [Plus-X] had increased in speed and that the grain had diminished to such an extent as to be negligible..above all, it was a true black and white stock with every minute tone in between.”

Like his first feature, Eraserhead (1977), Lynch wanted to shoot his film in black and white despite the popular diminishment of that format, and he was supported by producer Mel Brooks, who had fought his own battle to shoot Young Frankenstein (1974) in gray tone homage to the original Universal Studios horror movies. Lynch sought out Francis, who had taken a break from cinematography to write and direct, but enticed him back behind the camera with his vision for the film, inspired by his photography of Sons and Lovers (1960). Speaking of that film to American Cinematographer, Lynch described “the photography was about light and dark, and it had a mood. It had such a great look that it seemed only natural to hire Freddie.”

When asked about how his experiences as a director had reshaped his thinking about cinematography, Francis answered,

“I won’t work with a director unless I feel that I’m on their wavelength. The three or four weeks I need in preparation for a picture mainly consists of just talking to the director so I can understand what they want. A director sometimes needs help…The cinematographer is an executive of the production and has to run things for the director,” he adds. “You also have to read their mind and then get that up on the screen, because any good director has already shot the picture in their head and can see those images. They can be improved, but they are there.”

Watch the film, if you can find it, and I think it’s apparent that he was able to read Lynch’s mind. At least as much as anyone could penetrate that TM’ed noggin.

Francis won the BSC Award for his cinematography.

The Movie Breakdown

David Lynch gets it. He knows the cruelty of respectable people, and how they signal otherwise. He also knows that our imagination is stronger than any image he can create, so he builds suspense through careful compositions, sounds, and editing as The Elephant Man begins. This is how a biopic should be done.

The opening shot is an important moment in every film - how do we enter this new world, and what are we asked to notice? The eyes are the window to the soul - that’s why eyelights exist, to emphasize sympathy and understanding and help us to see our flaws. We are introduced to this late-19th-century Victorian London through a perfect pair of eyes, confronting us with a direct address. This is a photo of the mother, who was trampled by elephants while carrying her child.

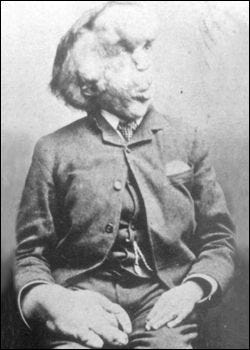

Lynch gives us mysterious and unsettling images to illustrate the background story, with hulking elephants emerging from the darkness intercut with wispy step-printed shots of the mother screaming and writhing in terror. It recalls the pain of childbirth but asks us to indulge in a personal mythology for the sake of dramatic attention. It is a world that is still torn between science and legend.

Anthony Hopkins (hard to believe he was ever this young!) plays respected surgeon Dr. Frederick Treves, introduced as he follows a Policeman into the Freaks exhibit of a traveling carnival. The officer breaks up the show and demands they leave town as it supports moral decay, so Dr. Treves finds his way to the proprietor for a personal show. If the opening sequence is the first sign of directorial authority, this build-up of anticipation is the final nail in the coffin. You are in the hands of a master.

The audience knows what they are in for, like P.T. Barnum’s suckers, we’ve already bought the ticket to the freak show. But in our hearts, we know that we are better than those other people who are there for unscrupulous reasons.

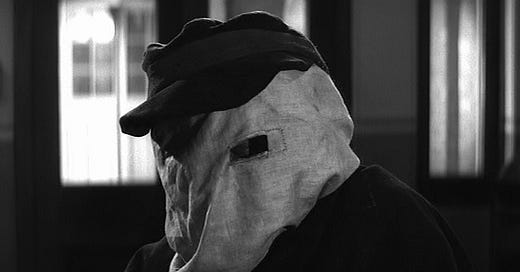

Like any good monster movie, Lynch draws out the suspense and builds up our anticipation to see the “freak,” keeping him in shadow and cutting away just as he turns to the camera, we must witness Hopkins’ reaction. His eyes grow in wonder as tears begin to cascade down his cheek. This might be the first compassionate human reaction that the physically deformed John Merrick (John Hurt) has ever received.

Dr. Treves rescues Merrick from enslavement by his cruel and abusive master, who until now has kept him in a cage. He checks into his hospital covered head to toe, continuing to deny the audience and orderlies a good look at him, then brings him to a show and tell with his society of surgeons, carefully framing to so that the movie audience only sees him in silhouette.

Lynch stretches out the tease as far as it will go, keeping the audience suspended in anticipation of another glimpse of the Elephant Man. We are finally allowed to see John once he has settled into his hospital bed, when a nurse unknowingly opens the door and screams in surprise.

Dr. Treves fights to keep him in the hospital when he discovers the he can read and speak, something the man has been hiding in his carnival appearances as a caged man-animal.

Little by little, we become used to his appearance as he becomes a source of curiosity to society figures, who start to visit for tea and conversation, once it is discovered that he can talk and read. There are more layers to him than we might expect. But is there something they are hiding? Do they really respect John or are they playing up their sympathies in order to feel better about themselves and their values?

Is this a case of Victorian-era virtue signaling?

But just as John is finding acceptance in high society, the carnival comes barking in the form of a hospital Night Porter (Michael Elphick), who uses his access to collect payments from curious bar patrons and exploit John, just like his former “owner” . The freak show is back on and more horrible than ever. As John tries to build a delicate model cathedral out of paper and wears a proper suit of an Englishman, the porter forces prostitutes to kiss him and humiliates the young man for amusement and profit. Literally playing the evil puppet master.

The carnival barker Bytes returns and pays the night porter to see the freak, kidnaps John and takes him to Belgium. He locks him in an animal cage with ravenous monkeys, but other carnival performers take pity on John and break him out. As he returns to Liverpool he is harassed by some children and accidentally knocks over a little girl, prompting a mob to chase him into a mens room. John collapses on the floor between urinals screaming “I am not an elephant. I am not an animal. I am a human being.” As an audience member it is almost too much to bear, but Lynch rewards our sympathies with a dignified third act.

Anne Bancroft plays Mrs. Kendal, a star of the stage, who befriends John with a gift of “Romeo and Juliet” then later invites him to the theatre. John is mesmerized by the performance, finally seeing what has been denied him, and is emotionally moved when Kendal dedicates the performance to him. This results in a rousing standing ovation from the very society that once looked at John with fear and contempt. It is a rousing moment, as all anyone really wants from this world is acceptance. John can hardly believe it as he slowly takes to his feet.

The stressful kidnapping and attacks take their toll on John, who finds peace with his impeding death. His entire life he has slept hunched over his knees, leaning forward as his head is too heavy for him to lie on his back.

As he returns to his room, finally feeling some form of acceptance, he removes the pile of pillows that have kept him vertical and alive each night, and lays down to his fate. He finally sleeps like a person, and as his consciousness fades away, his mother appears to him as if in a crystal ball, quoting Lord Tennyson in soothing tones, “The wind blows, the cloud fleets, the heart beats, nothing will die.”

BONUS VIDEOS!

Some video clips from the film to give greater context to these scenes, as well as an informative interview with David Lynch about the making of the film.