Sometimes, I’m an idiot. I don’t always see the power and beauty of a movie until many years or screenings later. I might be approaching a film with preconceived ideas of what it should be, or the film’s techniques catch me off guard. It might even be that I first see the picture in the wrong context or format, which diminishes the artwork. This is why I advocate for the theatrical experience when watching a movie for the first time, if possible.

We now have many ways to view films, but few genuinely respect the art form. We no longer have the movie palaces of Hollywood’s golden age, but in today's theaters, the picture and sound are pristine, and the stadium recliner seating is pretty damn comfortable. Even art houses have gotten a lot more comfortable for the most part. Keep your phones and iPads for the so-called “peak TV” drivel. Good movies deserve our full attention.

It’s hard to change our minds, but re-evaluating films and artists is part of an essential longstanding cultural realignment. We’ve all read horror stories about falling from grace, but today, I want to examine the opposite: what happens when a film we don’t like becomes good? (to us, at least) What could have changed if the film had remained static? (barring those unctuous REDUX and FINAL CUT versions).

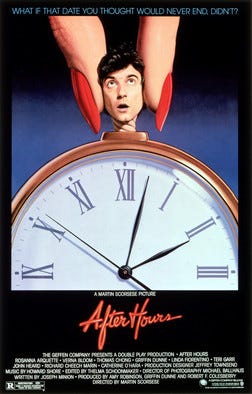

Many filmmakers have experienced re-evaluations of their work, but few as thoroughly as Martin Scorsese. After a powerhouse decade in the 70s that included Taxi Driver (1976), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), and Mean Streets (1973), the 1980s landed with a thud. Raging Bull (1980) and The King of Comedy (1982) both bombed and were far from their popular culture reassessments. Scorsese spent most of 1983 preparing to shoot The Last Temptation of Christ (eventually released in 1988), only to have the production fall apart on Thanksgiving Day. People were saying his career was over, and he was un-fundable. This was when he read the script for After Hours (1985), a comedy that follows computer word processor Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) as he navigates one night in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood that spirals out of control. A Sohodyssey, if you will.

I was introduced to this movie via a scene shown in a Freshman filmmaking class - it starts with a yellow cab rounding a corner, followed by a focus rack to Paul Hackett’s hand in the foreground. Scorsese stays with Paul’s hand as the cab approaches, and he jumps in the back, saying, “I only have $20. Can you break that?” No problem, says the Driver, and they speed off into the night. The camera under-cranks the exterior driving shots for a comical sped-up effect, closer to the Keystone Cops than Marty’s own Taxi Driver, and inside the back seat, Paul is flung to and fro as the wind whips around him from the open windows.

The first thing that irked me about this movie was when Paul puts his only $20 bill in the tray that connects to the driver - the bill predictably flies out the window, and he is left alone and penniless in Soho as his cab angrily screeches away. Even though the conceit annoyed me, the scene's power stuck with me over the years - Scorsese had designed the shots to fit together like a puzzle - he ends the chaos with a slow-motion shot of the lost $20 bill fluttering through the night air.

The teacher who showed us this clip had a clear lesson in mind - to show us a scene that has a compelling story with an objective, an obstacle, and a conclusion, made with style and clocking in at a mere two minutes. The driver has a small role but a clear sense of character - and the streets take on a lonely personality of their own.

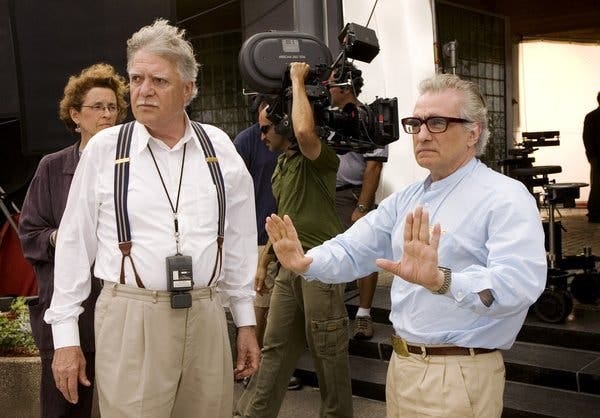

Inspired by this class experience, I tried to watch the film several times over the years but was initially hampered from enjoying it by a lousy VHS transfer, making it look over-lit and washed out. I tried again on DVD but could only get so far into it because I became so embarrassed for the characters that I could not enjoy the awkward comedy alone at home on the small screen. I chalked up my reactions to the idea that this was a movie from a great artist’s fallow period before he rediscovered his groove with Goodfellas (1990). So when I recently got an invitation to attend a 40th-anniversary film screening, complete with a Scorsese/Griffin Dunn Q&A, I was excited to re-approach the movie, this time in a theater with an audience.

This was a gold-standard screening, with a respectful industry audience (no talking or cell phones!) and a stunning DCP projection, which elevated the look of the film beyond any previous viewing experience. The grain structure of the 1980s-era film stock was apparent but not distracting, and the lighting in the night exteriors and dive bar locations was more subtle than those early video transfers could ever capture. The camera moves on the dolly and Steadicam give an exciting visual jolt, whipping the audience around like the hapless protagonist, extra impactful on a large screen. I thoroughly enjoyed the movie for the first time after decades of attempts.

This was Scorsese’s first film working with iconic German cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, who had survived the drugged-up sets of the brilliant Rainer Werner Fassbinder, so he must have felt right at home in Bad Old New York’s heyday. He went on to shoot many more films for Scorsese, including Goodfellas (1990), Gangs of New York (2002) and The Departed (2006). At this screening, I finally could appreciate the nuance and seductive nature of his lighting for both wide empty night exteriors and intimate close-ups.

The QUESTIONS and ANSWERS

I’ve attended many unsatisfactory or embarrassing experiences at director talkbacks over the years, but this one was illuminating and transcendental. Scorsese is both a technical and emotional filmmaker with an endless knowledge of the medium and history. He and the film’s star/producer Griffin Dunne recalled so many details from their set adventures that it was hard to believe it had been 40 years.

Scorsese started with his mind-state at the time, which was a feeling of failure. He had just moved back from L.A. and was living in a downtown loft on Duane street, wondering if his career was over. He approached After Hours as a chance to go back to basics and re-learn how to make a lean and mean film. He storyboarded every shot, essentially pre-cutting the film in his head for maximum impact. He kept the visual plan as simple as possible but used fast-moving shots to add impact or show the importance of a character’s revelation. The filmmakers then gave one example of how they used the Steadicam to match the “hero’s journey.”

The film opens and closes with shots moving through Paul’s corporate office environment, but the pace and style of the movement reveal the transformation the character has endured. The opening shot of the film is surprisingly fast-paced - the camera flies through an office crowded with computer terminals and busy people, and we hear typewriters and phones ringing off the hook. The shot lands in a close-up on Paul, who is training a new hire on the intricate details of data entry. The young trainee cluelessly says that he doesn’t plan to stay long, he will soon be moving up the corporate ladder, which prompts Paul to look around his environment and have a mini-existential crisis examining his life in the cubicle-centric world. We get a series of shots from his point-of-view that drive home the myriad ways office workers cope with the drudgery through decorations and inspirational maxims. The sequence ends with a slow-motion shot of security guards closing the building’s entrance gates as Paul and the last workers exit. This guy needs to get his groove back.

Scorsese confirmed that he had total support from the producer David Geffen, who told him to take his time in the edit to come up with the perfect ending. After his harrowing night caper, Paul returns to his office as a changed man. He accepts that his boring life isn’t as bad as he thought, now that he’s tasted the fear and anxiety that comes with adventure. He sits down at his computer and lets out a sigh, and the camera gently floats away from him and elegantly circles the rows of desks and computers as other workers arrive and the office comes to life for a new work day. The emotional impact of the two camera moves is undeniable - enjoying your life is all about finding the right perspective.

In the Q&A, Scorsese talked about filming the last shot of the movie with Steadicam operator Larry McConkey. The director had a record player on set blasting Mozart’s Symphony in D Major, K. 95 as they rehearsed the shot, but he was unhappy with the results. After one take Scorsese said, “Listen to the music, let the music guide the shot.” The company broke for lunch and McConkey rehearsed on his own to figure out the complicated moves that would match every note of the soundtrack. After lunch, they nailed the shot, and Larry so impressed the director that he went on to shoot the famous Goodfellas Copacabana entrance, long held up as the perfect Steadicam shot.

It feels like people have forgotten the power of the theatrical film experience. We must remind ourselves to take breaks from our lives and give in to the moment, letting the film take control as we sit in the dark. No phones. No outside world butting in. Everyone sees themself as a multitasking genius these days, but multi-screen living is a recipe for a forgotten life. Nothing will stick. Nothing will be impactful.

I don’t want to go down every rabbit hole of the Q&A, so if you would like to hear more from the horse’s mouth, here is a 2022 Fran Lebowitz interview with Martin Scorsese discussing After Hours. Enjoy! Marty sure did!

sohoddessy...genius.