Akira Kurosawa's Deep Focus

The art of pushing long lenses to their optical limits.

Modern society is so self-involved that our obsession with shallow focus imagery is hardly surprising. When one character stands out against the blurry background, we are tempted to call the shot “cinematic” and the person “heroic.”

But a real hero shares their focus with the community. Just ask Akira Kurosawa, who knew that the mantle of “hero” could be picked up by a lowly farmer or abused by a haughty ronin samurai.

I used to think that Barry Lyndon (1975) was the world’s best film - it combined pristine compositions, realistic candlelight, and real-world sets in a wry, underhanded comedy that mocked social climbers everywhere. The film’s critique of a static upper class that conspires to acquire all the kingdom’s wealth using nameless peasants as fodder spoke to my younger self.

Kubrick was the original cinematic cynic, after all.

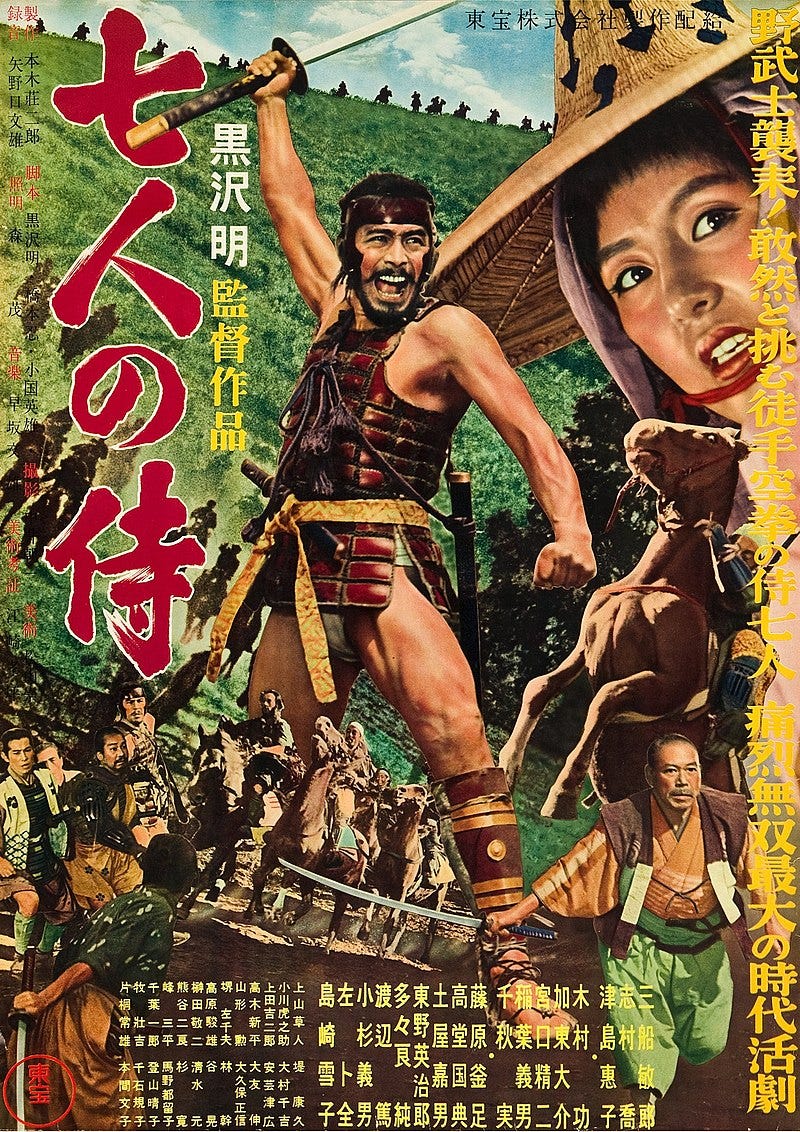

But the older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve gravitated towards Seven Samurai (1954), a story of villagers putting aside their differences to save themselves from roving bandits.

As I study the film, I am amazed by the dynamic intensity in Kurosawa’s use of long lenses. He creates compressed compositions that keep multiple layers in focus, unlike the typical Hollywood close-up technique that separates an actor from a blurry background.

Kurosawa builds a continuous series of seven shots, even while composing in the boxy 4x3 aspect ratio. He places the samurai at different depths, shooting with enough light to close down his T-stop to make each image layer appear focused.

SEVEN SAMURAI

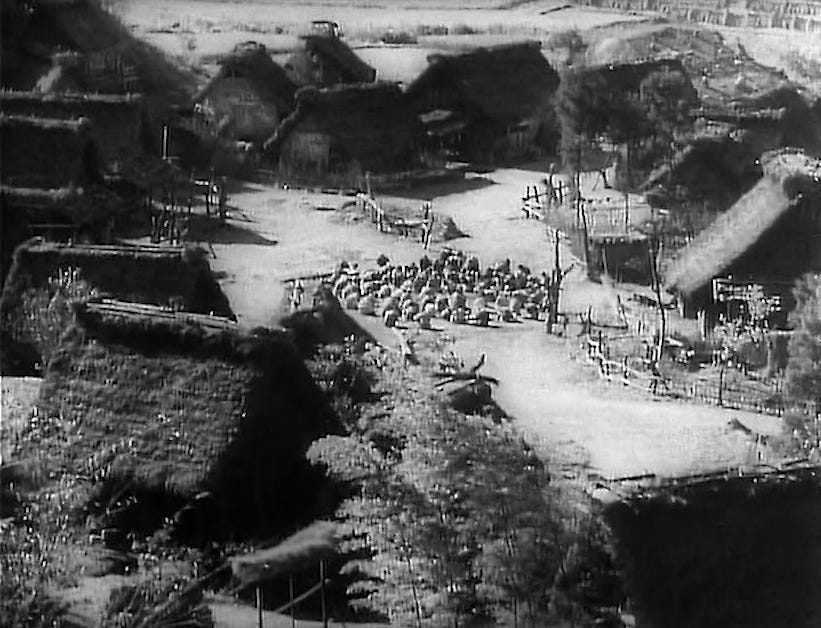

Seven Samurai opens with inky black smudged exteriors, the sounds of a galloping horde turn into bandits approaching a village. The camera towers over the men on horseback, peering from a ridge to a circle of thatch huts below. The long lens compression makes the village look more present and vulnerable and intensifies the shots of bandits on horseback.

A local farmer overhears their plan to return and steal their harvest and runs to inform his neighbors.

Everybody freaks.

Kurosawa skips ahead to the town meeting with a series of axial cuts. We see dozens gathered in a circle, starting high and wide over the village square. The camera pops in directly on the z-axis, one shot at a time, until we land in the middle of the group, surrounded by layered medium close-shot compositions.

He gently leads the audience into a delicate situation, ultimately placing us with the farmers, getting the short end of the stick. Some of them despair and suggest that everyone kill themselves and give the bandits their crops. Others cry. Some want to fight, but they don’t know how.

Who can’t identify with that? Especially when we can see each side of the argument in focus. The long-lens skinny angle of view compresses the villagers on top of each other, magnifying the tension.

When you shoot overlapping layers with a telephoto lens, the relative distance between subjects and the camera is lessened. This means that each person is projected at a similar size in these shots and seen as equal. They feel closer together, and more vulnerable.

In the reverse-shot angles below, you can feel the power of Kurosawa’s long lens choice.

If you compose a two-shot with a wide lens, you have to account for a wider angle of view, so the camera must be closer to one subject and further from the other, making the background layer appear much smaller than the foreground. In the still below notice how much larger Mr. Thatcher’s head is in the foreground, closer to the lens.

OK, back to the Samurai story.

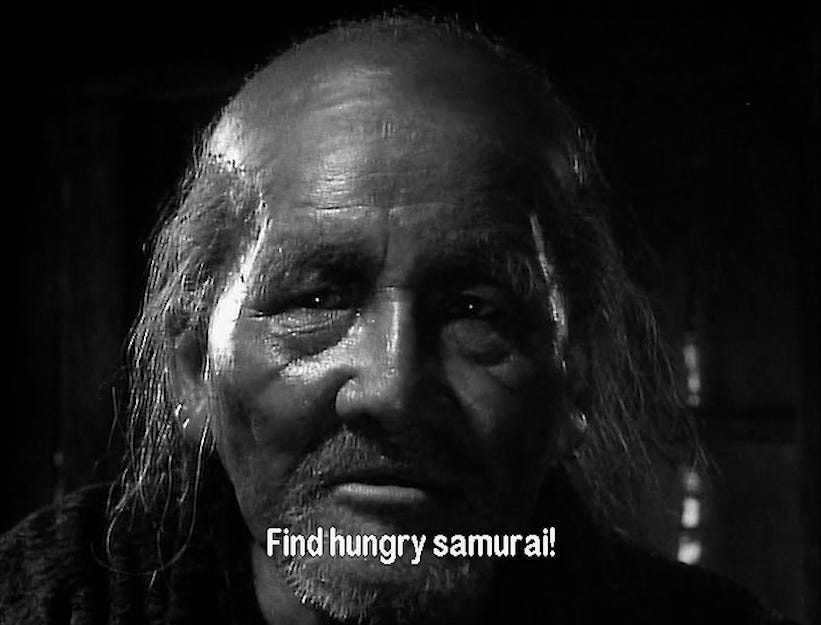

After much argument, the group marches across the river to consult the Village Elder, who directs them to find a group of samurai for protection. “But all we have for payment is rice,” they protest. The elder calmly responds, “Find hungry samurai.”

So off they go to find some hungry samurai. After many rebuffs and taunts, they build up a group of seven ronin only to return to an empty village. Everyone is hiding, terrified of the people there to save them. Could a movie be more truthful?

As the samurai gain the villagers’ trust, Kurosawa takes the time to create real characters and familiarize the audience with the terrain, building stakes for the climactic battle. We get enough of their personality to like them, especially the ridiculous liar played by Toshiro Mifune.

The characters are so well communicated that my then-six-year-old daughter watched the entire film. She loved “the silly Samurai!” (Mifune), the way he was always boasting and peacocking, but ultimately becoming one of the most heroic deaths in movie history.

This 1954 trailer has a great introduction to each samurai starting at 1:35:

Lens length and depth of field:

Everyone knows a wide-angle lens can help give your shots deep focus, but what about longer lenses? Are we not doomed to watch Jason Borne-style shallow focus shaky cam every time we pop on a 135mm?

Only one distance from a camera can genuinely be in focus at a time. That’s just optics. So, how do we achieve deep-focus images, again?

A quick review:

A lot depends on the lens's aperture – the larger the diameter, the more shallow your depth of field will be, and conversely, the smaller your iris, the more in focus your image will look.

When the out-of-focus dots (bokeh) become so small that they appear to be in focus, it creates the illusion of deep focus in an image.

Another factor for depth-of-field is focus distance - the further you place the actor or subject from the camera, the greater the acceptable focus will appear in the frame depth around them. This is helpful if you have a group of people you would like to frame in conversation but not distract the audience with focus changes from one to the next.

Wide lenses generally create more depth of field but can stretch a space out, making characters appear abnormally distant from each other. Kurosawa created sharp bold shots of compressed intensity, guiding the composition with highlight and shadow.

This brings us back a few decades to Gregg Toland, ASC, cinematographer of Citizen Kane, who worked hard to sharpen image quality in motion pictures. Unlike Toland’s work, Kurosawa tended to limit his depth of field to the people in the frame, allowing backgrounds to go soft.

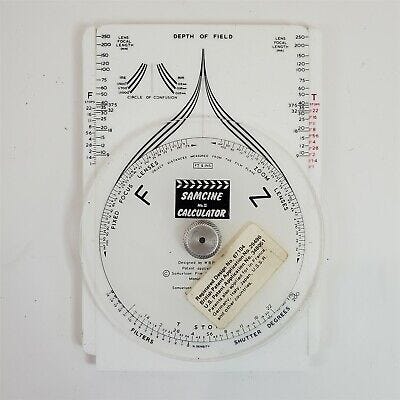

Focus charts and depth-of-field calculators help filmmakers determine how much distance they can count on looking sharp. But remember, you always need to test your specific lens set and camera format to be sure.

The ASC also publishes a handy manual that boasts pages of depth-of-field charts for reference.

I am a complete film noob but Kurosawa's compositions in Seven Samurai have me mesmerised. I wanted to understand what was special about his technique and that's when I came across your piece. Thank you so much, this was so well explained!

Insightful!

I need to revisit Seven Samurai!

Bravo!