Have you been doing your best refracting lately? Is there anything else you could do to bend light creatively?

Today’s movies favor paper-thin focus with blurry backgrounds aided by ever-larger sensors and super-speed lenses, so looking back to Hollywood’s golden age cinematography can bring a visual jolt, especially regarding Samuel Goldwyn’s camera superstar Gregg Toland, ASC – best known for a little film called Citizen Kane (1941).

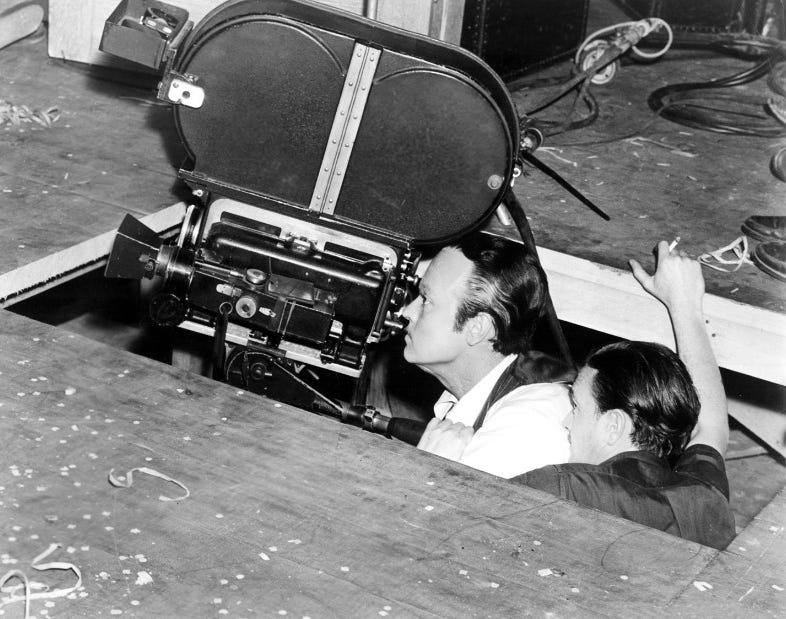

Toland started as an office boy, then camera tech, and worked under many great mentors to become the highest-paid cinematographer on the studio lot, winning an Oscar for William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights in 1939. When he heard that boy wonder Orson Welles was jumping from stage to screen, he knew that the young director would need his expertise to pull off one of the most ambitious shoots of the era.

Toland describes their initial working ideas in an article from American Cinematographer (February 1941):

“Citizen Kane is by no means a conventional, run-of-the-mill movie. Its keynote is realism. As we worked together over the script and the final, pre-production planning, both Welles and I felt this, and felt that if it was possible, the picture should be brought to the screen in such a way that the audience would feel it was looking at reality, rather than merely at a movie.”

Approaching an epic story of a public figure who can never collect enough trophies, he knew he needed to keep deep, wide shots sharp and focused to visualize Kane's growing accumulations and shrinking associations. The only problem is that a camera lens can only focus on one distance at a time.

What’s an ambitious visual storyteller to do?

Enter sound stage left – our friend, Depth-of-Field - aided and abetted by his buddy Circles-of-Confusion. Given the physics of refraction, these two concepts allow our shots to look more in focus than would typically be possible.

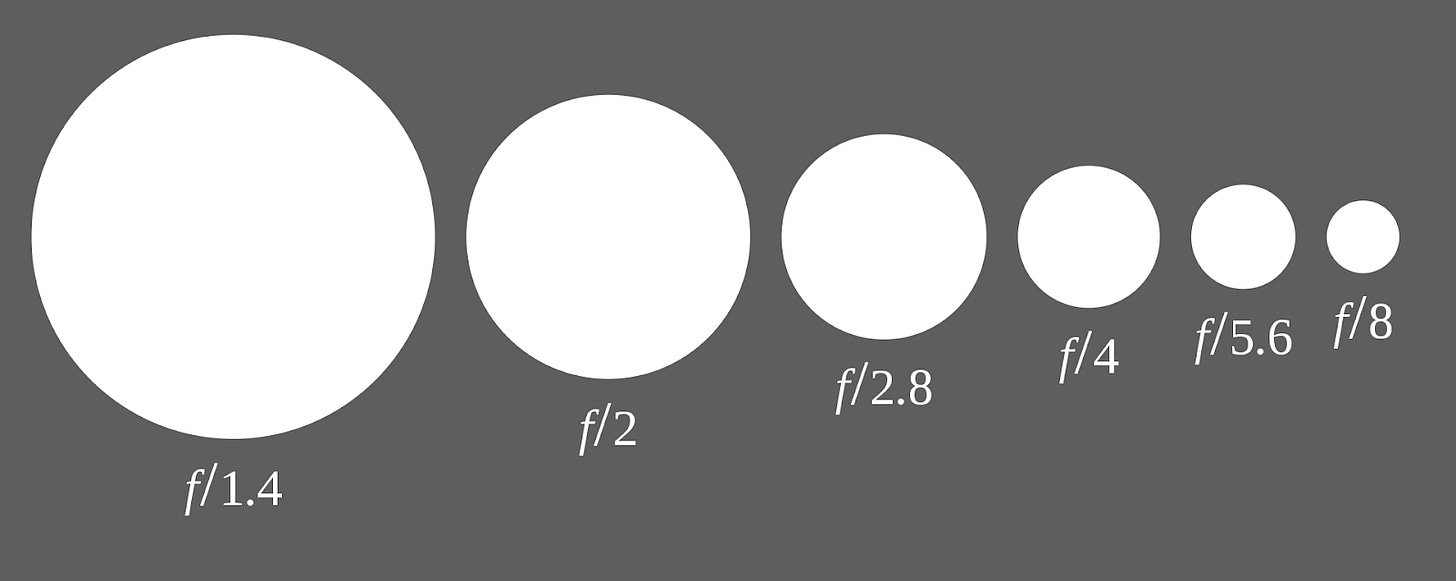

When we set focus on the lens barrel, it signifies a certain distance, like 5’ or 10’ from the image plane (the film or digital sensor). If our aperture is wide open, especially on a super speed (f-stop 1.3 or larger), that distance will be the only part of the shot that looks in focus.

In the illustration below, we see the middle object distance is in focus because the light rays from the lens converge at the image plane, creating a tiny focused dot. The top object is closer than the focus plane, so it converges behind the image and the converging light beams take up more of the sensor area which we see as a big blurry circle. The same goes for the bottom object distance, when light beams converge in front of the focus plane they continue to diverge until they reach the sensor plane and are larger than a sharp focus point.

If you close your iris down, stop by stop, the image will start to look more and more in focus. The closing iris shrinks the size of the out-of-focus “bokeh” dots that make up the blur, which confuses our eye into seeing them in focus.

So, to sum up, Deep Focus is an illusion made possible by the selective use of lenses (wide angle), aperture size (small f-stop diameter), and focusing distance (the farther, the better).

Wide-angle lenses like 18mm or 24mm generally create shots with more depth of field, especially when focusing farther away from the camera. When you combine that with an F-stop closed down to f-11 or f-16, you can be sure to get your frame in solid focus. This was Toland’s approach to create a hard-nosed visual treatment of Kane, leaving no detail unfocused.

Lenses in the 1930s were softer than modern glass, with more aberrations, and lacked the sophisticated anti-glare coatings we now take for granted. To make matters worse, film stocks were much less sensitive than our current film and digital sensors.

Toland worked with Kodak’s Super-XX black and white stock with a sensitivity of 100 ASA (today known as ISO). We currently use that sensitivity for day exterior, not studio setups. He had to use a tremendous amount of light to close his f-stop to achieve deep focus imagery, creating multi-planed compositions with clear elements that allowed the audience to choose which part of the frame to focus on.

Again, in American Cinematographer, Toland describes his process:

“First, we were using, as I have been for some time, lenses treated with the Vard "Opticote" non-glare coating. In view of the considerable discussion that has arisen since the introduction of these treating methods, I may mention that so far I have found this treatment not only beneficial, but durable. Depending upon the design of the lens to which it is applied, it gives an increase in speed ranging between half a stop and a stop, while at the same time giving a very marked increase in definition, due to the elimination of flare and internal reflections.

Secondly, due to the nature of our sets, and the lighting problems incident to our use of ceilinged sets, we were, even before we changed from Plux-X to Super-XX, making considerable use of arc broadsides. In addition to the greater penetrating power of arc light as compared to incandescent, this gave us a further advantage, for the arc is unexcelled in concentrating the greatest illuminating power into a comparatively small unit…The use of these lamps made it possible to use considerably smaller lens apertures than would otherwise have been the case, while still keeping to satisfactorily low illumination levels, and using surprisingly few lighting units.

It was therefore possible to work at apertures infinitely smaller than anything that has been used for conventional interior cinematography in many years. While in conventional practice, even with coated lenses, most normal interior scenes are filmed at maximum aperture or close to it — say within the range between f:2.3 and f:2.8, with an occasional drop to an aperture of f:3.5 sufficiently out of the ordinary to cause comment — we photographed nearly all of our interior scenes at apertures not greater than f:8 — and often smaller. So the scenes were filmed at f:11, and one even at f:16!”

Critic André Bazin called this audience empowerment the democratization of the frame – viewers oversaw their interests instead of being led around the scene by edits, blurs, and focus racks. Deep focus allowed the audience to participate in creating meaning through their visual detective work.

Giving an audience that much power over your shots is always a risk as they could get lost in the details of each frame. Camera placement was critical for Toland to act as a visual guide, paired with nuanced and shadowed lighting. Citizen Kane presaged many of the dark lighting techniques that would come to be known as the film noir style.

Our eyes are naturally attracted to movement, framing, brightness, and focus, so a combined approach is the best way to create the illusion of choice but still confirm that we understand what is important. Toland used several other visual strategies to emphasize compositional storytelling – framing devices like doorways and windows and power dynamics illustrated by positioning actors in triangular formations.

Long Takes

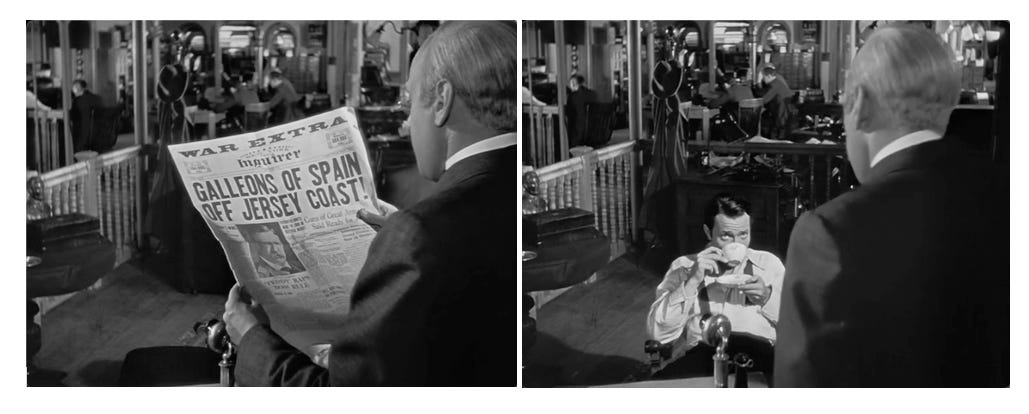

Toland and Welles shot scenes by moving and reframing the camera rather than relying on edits as the primary driver of the story. A great example of this technique is seen in Kane’s newspaper office as he is confronted by former guardian Mr. Thatcher, who is angry that The Inquirer is attacking his company (Kane is also a major shareholder in the company he’s attacking).

The scene/shot begins high over Thatcher’s shoulder, looking down at Kane like a little boy; his frame size is also diminished by using the wide-angle lens, which emphasizes the foreground over the background on the Z-axis. With the use of deep focus, we can make out the background of the office, where reporters and copy editors labor away on typewriters and in conversation. Toland keeps Kane brighter than the background, so our attention stays on him, but we can see the room in detail.

Welles blocks the scene with Kane’s assistants barging in to deliver a telegram (“No war in Cuba, STOP. Girls delightful”). They stay in place to compose an upside-down triangle that points to the Boy Wonder as he conjures a war in Cuba (“You provide the prose poems, I’ll provide the war”).

Yellow journalism at its finest.

As their conversation heats up, Thatcher moves in and sits down, bringing the camera with him.

Kane takes control of the scene by defending his newspaper’s fight against corruption, and the camera lowers to a heroic angle. He is no longer the little boy that Thatcher can control.

This moment presents another example of the power of deep-focus shooting – we now become aware that all the typing and talking have stopped, and everyone in the office is watching their boss, frozen in their tracks. We read the facial expressions and emotions, making the scene feel authentic.

The scene ends with Kane helping Thatcher into his coat, a visual reversal of Kane’s childhood being dressed and groomed by Thatcher. The old man’s last retort is to mock his business acumen, pointing out that the paper is losing a million dollars a year. Kane replies that he intends to keep losing money to fight the good fight, and might have to close the office in…60 years.

Toland never worked with Orson Welles again (unfortunately dying of a heart attack at the age of 44). Still, he profoundly affected the director’s shooting style, and Welles’ subsequent films utilized wide lenses, deep focus, camera movement, and high contrast. In many ways, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Touch of Evil (1958) look like Toland could have shot them.

No offense to Stanley Cortez and Russell Metty, the cinematographers of those films, respectively.

BONUS LINK!!!:

From the ASC American Cinematographer archive – the February 1941 article written by Gregg Toland detailing his approach and visual strategy for Citizen Kane:

You might like this little thing I did some years ago. http://thechoicestcut.blogspot.com/2009/11/photography-and-four-dimensions.html

Wonderful, Alan. Love it!