Vampires: Real and Imagined

"The world is a vampire sent to drain, Secret destroyers hold you up to the flames" The Smashing Pumpkins

Total immersion cinema creates a dream-like state for the audience, lulling us into the world of the film by making it feel as real as possible. The Brutalist (2024) and Nosferatu (2024) achieve this magic trick through detailed and consistent set design, shot structure, lighting, music, and superb acting. Both period pieces benefit from being shot on film as that format is still the highest quality medium available and matches our memories of mid-20th-century films. Both movies built detailed and mysterious sets and used existing locations to their full advantage, moving their cameras through spaces like explorers rather than artists. The sleight of hand editing and music punctuate the drama with forceful denunciations against banality. Both films convinced me that vampires are real, even if only imagined.

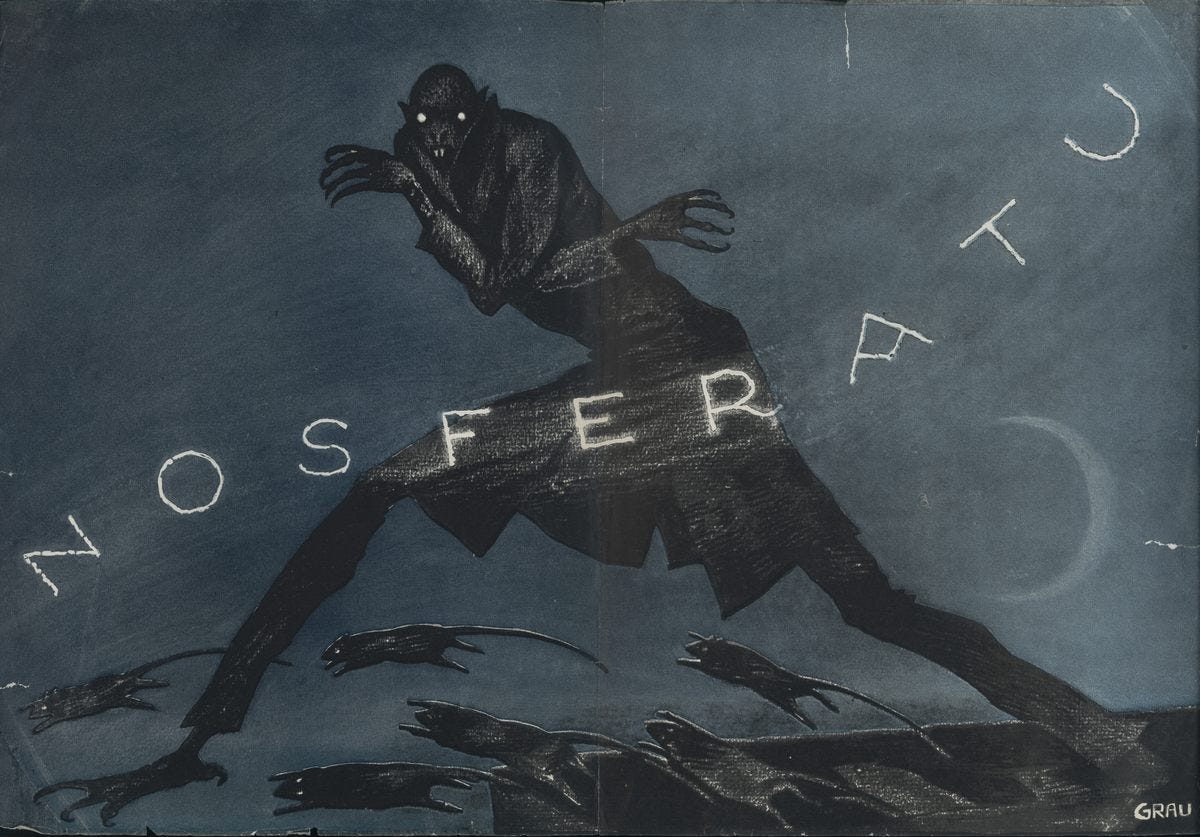

We are all afraid to die and be forgotten. The horror genre knows this well and filmmakers in the century since the original Nosferatu (1922) made its illegal way into the world have found consistent work. It’s hard to imagine a cinematic world without that film, which was ordered destroyed after a copyright lawsuit brought by Bram Stoker’s widow. Thankfully some copies survived and inspired others to follow its dark path.

The original Nosferatu got under our skin with stylized high-contrast images, mysterious locations, and most importantly an irresistible villain. Movies don’t work without a compelling antagonist, especially horror. Freddy Krueger. Jason. Michael Meyers. Mother from Psycho (1960). These characters worked seamlessly into our cultural psyche because of their distinctive presence, but they have stuck because they are real. We have dealt with these people in school or at work. They are bad dates. They are our bosses or politicians we didn’t vote for. They are the unknown figure walking towards us on a dark street as we hustle home. We can always relate. We are wired for fear.

Count Orlok takes many cues from Stoker’s Dracula but becomes more sinister by resembling a corpse rather than a count. He is walking death. Robert Egger’s remake updates this character perfectly, emphasizing his rotting body only after a perfectly drawn-out introduction that keeps the figure hidden in shadow. Bill Skarsárd’s Orlok performance is mesmerizing and hypnotic, pulling his co-stars into his web of darkness and deceit. He reminded me of the Russian mystic Rasputin, larger than life so that he can’t be taken in at once. Each piece of the character puzzle we get makes us want to see more. The more we see, the more we believe.

Watching The Brutalist was an equally entrancing experience, the opening shots setting up revelations that would not occur until the end and creating detailed characters that you could swear were real historical figures. It plays like a bio-pic but the first notes of the overture tell us it will be a horror film in disguise, followed by the triumphal horns that hint at a great achievement to come.

Adrian Brody has been rightly awarded for his gut-wrenching performance as architect Làszló Tóth. He is a tortured Holocaust survivor, lost in a new country and separated from his family, finding solace in prostitutes and heroin. Still, I want to focus on the vampire of the movie, Guy Pearce’s Harrison Lee Van Buren Sr., who is introduced as an antagonist and then reappears as a benefactor “savior.”

Van Buren is an American robber baron who always gets what he wants and sees his fellow citizens as servants, or worse. Like Dracula in his Carpathian castle, he lives far from the dirty city on a bucolic estate, secluded from daily life. His introduction to Tóth is a surprise as Van Buren Jr. has secretly hired the architect to redesign his library as a birthday present. Tóth tears down the stodgy drapes and replaces them with a single-action lever-powered shelf system that protects the books from damaging light and dust with a perfect modernist reading chair in the center. Van Buren Sr. is angry to find his sanctum brutalized and kicks the construction crew out, only to later search out Tóth, who is now shoveling coal to survive. The industrialist has come to his senses and done his research, discovering the architect's Bauhaus roots he asks him to design a community center in honor of his mother that he calls The Institute. Tóth doesn’t want a handout but to earn the commission with his design ideas, the details of which he keeps to himself.

The relationship between artist and patron has a long fraught history. What autonomy does one have to give up to get funding or success? History is filled with examples of patrons from Kings and Emperors to the Catholic Church and many other people and institutions. Some cultural good has come from these relationships, as any walk through a major world museum will confirm. But there is always tension when one side has the money and the other only skill.

Throughout the film, tensions build between Van Buren and Tóth as conflicting demands are placed on the building and the budget runs over. The architect is involved in every small detail but his influence is questioned and fought at every turn. Hack middlemen are brought in to dilute his ideas. Costs are saved to the point where he forfeits his commission to keep the proportions of his original design. After surviving the Holocaust he is forced to ignore his Jewish identity and build a Christian chapel as the centerpiece of the community center.

One of the most arresting visual sequences involves a trip the two take to an Italian marble quarry to find the perfect altar slab. The shots are wide with small figures ascending into the cloudy mountainside. After they find their stone a party breaks out to celebrate and Van Buren watches Tóth succumb to his favorite means of avoiding his pain, heroin. The millionaire takes the opportunity to rape his artist and put him in his place, asking why Jews like him always make themselves victims. It is the culmination of the relationship, akin to the vampire’s bite.

The film ends with Tóth’s work being recognized at the 1980 Venice Biennale but lacks the triumphant feeling evoked by the opening horns. He is now being sucked dry by the business of architecture and history, being put in a box on the shelf. After three hours of gorgeous Vistavision 35mm 8-perf images blown up to 70mm we see this sequence shot on standard definition video, lacking color detail and nuance. This helps update the story from mid-century to the video age but also confirms that with progress comes setbacks. The architect sits mute in a wheel chair, watching his legacy enshrined. At this point, we discover the meaning of his fight through the words of another - the proportions of the Institute were modeled on his concentration camp cell. Hitler, the ultimate vampire of the 20th century still had his fangs in him after death.

Brutal.

Brilliant writing about the brutality and blood sucking all artists endure. Thank you for opening our eyes. Heaven help us!