I don’t always go for required mid-winter resolutions, as I find that any time of year is a good time to work on my many flaws. However, one particularly good New Year’s Eve resolution came to me in a flash as 2019 was ending - I vowed that 2020 was going to be the year I became a filmmaker for real. Not just a cinematographer who occasionally directed. This was going to happen. At the time, I thought that meant that I would finish editing the two back-burner documentaries I was making between shooting and teaching gigs. Little did I know what that year had in store!

The universe listened and gave me what I wanted, but not in the way I had anticipated. First, with COVID-19 raging on campuses I had to learn how to teach cinematography, an inherently hands-on process, via remote computer. Then my shooting work disappeared and I had to become an editor and producer, which led to me bringing my first feature film to completion and distribution, not just shooting and showing up for color correction after the edit. Then a colleague offered an opportunity to teach a class that doubled as a directing job for a series of short films made with the senior film students. As we were remote editing that spring, a feature film script landed in my lap that took place at a college and I was able to parlay that into directing my first feature, STARGAZER, bringing my newly trained graduates along for the ride.

I don’t believe in the Secret. I don’t think that the universe conspires for or against you. However, I believe that if you put yourself in the right mindset, you notice opportunities that you could otherwise miss. I have also found that you need to think broadly rather than restrictively if you want to “manifest” your “destiny.”

When I joined the film business in the mid-90s I had a very narrow vision of success. Outright naïve ideas of what I would be able to accomplish in film. I have learned valuable lessons along the way as I worked in many different departments from production to lighting to camera, which has forced me to learn skills that made me employable. In hindsight, this has all been useful and helped form me into a better filmmaker than I would have been right out the gate.

The choices I was forced to make as I trained formed my filmmaking core. When I prioritized my future over my present I got ahead eventually and reaped rewards. When laziness overtook me between freelance jobs I stagnated. It took years to find a balance during off time and be productive.

Which brings me to a better way to think about New Year's resolutions.

My favorite New Year metaphor is the parable of a young Heracles at the crossroads, contemplating how to go forward. He is approached by two allegorical figures, Kakia (representing Vice) and Arete (Virtue). Vice goes first (of course!) and seduces him with tempting offers of immediate and easy pleasure, but Virtue puts up a fight by promising a tougher but more rewarding life, perhaps even eternal glory.

So here we are, thousands of years later, still talking about the guy. Who do you think won?

Was Heracles the first subject in the Marshmellow test? That famous experiment where children were given the option of one marshmallow now or two later. What I love about Greek mythology is how well the gods and heroes represent us, normal humans. We all struggle to delay pleasure, just like the son of Zeus (who never seemed to delay pleasure, btw - “it’s good to be the king!”). We all need constant reminders of how to build a better future for ourselves, our careers, and the world at large.

The story of Heracles at the crossroads has come in and out of favor from its beginnings in the classical era in Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Aristophanese’s The Birds. Many artists have taken up the dramatic moment as a theme in painting and printmaking as it perfectly lends itself to single-image storytelling. In filmmaking, we can take as much time as we need to build up to a moment, but the classical and Renaissance artists had to be precise with the moment. They emphasize the humanistic theme of the choice between a contemplative life and an active life.

Albrecht Dürer imagines Hercules (the Roman name) ganging up with Virtue to attack Vice, who sits with a satyr (1498):

I love this image of Virtue preparing to wallop Vice as we tend to think of Vice as the violent one. It almost looks like Hercules is intervening between the two (and he certainly hasn’t skipped leg day recently). The figures form a triangle, the strongest shape for drama, and each figure is positioned to create maximum imagined movement. Getting the audience to build their own story on either side of the depicted moment in time is the key to this type of storytelling. It’s more than illustration, it’s an invitation to participate in the narration.

Paolo Veronese took on the same moment six decades later in Venice, The Choice Between Virtue and Vice (1565):

Here we get another action moment of Hercules embracing Virtue, but Vice is hot on his tail, concealing a knife and statue of a sphinx. Despite the movement, this moment feels less dramatic as he’s already made his virtuous choice more definitively. Compositionally it initially plays in more of a line than a triangle, with the viewer’s eye moving along the figures and landing on the knife. The white silk outfit draws our eye to the center of the conflict, with the arms and eye lines helping lead us through the darker corners of the painting. But on a deeper reflection, a triangle emerges between the figures and the caryatid-like statue on the top left, whose gaze is emphasized by the lines of clouds and branches. Above the statue is written “Honor and Virtue Flourish after Death” which neatly sums up the theme of living for your future (dead!) self.

Three decades later the Italian Baroque painter Annibale Carracci was commissioned to paint The Choice of Hercules (1596) by Cardinal Odoardo Farnese for his family’s palace:

In another triangular composition, the figures stand out from the darker background and give the viewer a clear understanding of the stakes. Hercules is centered and sitting in a more contemplative position than the other paintings. Dramatically this sets the audience up to lean in and try to figure out what he is going to choose. Virtue is pointing the way up the mountain but Vice is wearing a seductive and skimpy outfit that barely conceals. Which way will he go? The palm tree behind him hints at his future military victories, and at the top of the steep mountain path waits Pegasus.

I’d say a flying horse is a pretty good reward for not eating a marshmallow.

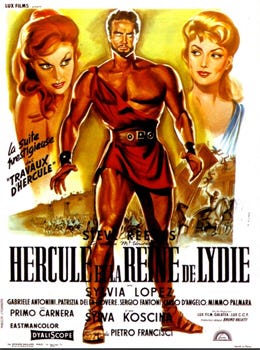

Not to forget Hollywood, here is one of many posters for the old Steve Reeves Hercules Unchained that plays with the man-with-a-choice moment:

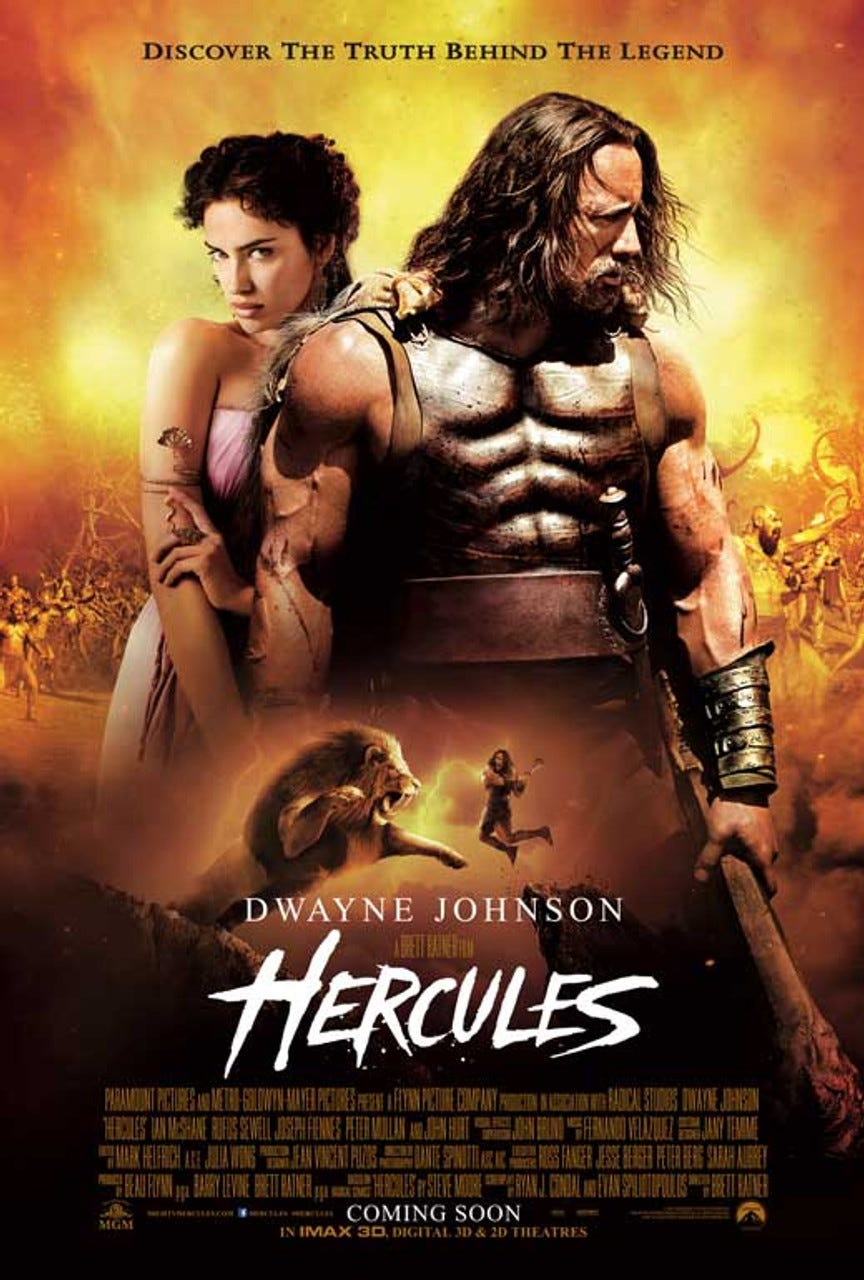

It doesn’t quite have the same artistic sensibility, and both women look like they represent Vice, but I do see dramatic potential. Unlike the more recent Hercules (2014) poster:

Where is the choice? Who is this for? Why did no one stop this?

As we gear up for another year, we can think about what will help us achieve our goals. It will often be the things we don’t want to do, but it will be worth the pain. For my part, tonight I’m going to embrace virtue and see Agnes Varda’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). It might not lead to eternal glory, but should help raise my filmviewer virtue meter by a few points.

This is a delightful meditation, a perfect way to start the new year. Do we have the will to do our best work? Might we settle for shallow and vicious pleasures? Turns out we’ve been turning this over in our collective mind for quite some time. As the co-writer of a script that became your first feature film, I attest to your patience and virtue. You’re a consummate stargazer, Alan McIntyre!